Earlier this year, the popular Danish television series The Legacy featured an architectural model for a striking new (fictional) museum. With jutting cantilevers, large windows, and a folding elevation, the model looked as though it could have been a real-life proposal for a cultural institution designed by a famous architect.

And, as Dezeen recently reported, it was! The Legacy‘s producers commissioned Julien De Smedt, founder of JDS Architects in Copenhagen, to design the museum model, which becomes the center of a new plot line in the third episode of the 10-part series.

photo via Dezeen

The serial drama focuses on a famous artist’s family members, who inherit her fortune after her death—which they then spend on building a brand new museum on the family estate. De Smedt’s design for the show was constructed on a much larger scale than it would be in real life, since the producers wanted the audience to have a better look at its contemporary design. According to Dezeen, De Smedt was chosen because the show’s producers wanted a model that looked like an art piece to convince the audience that it was possible to build a museum in a quiet locale.

The appearance of De Smedt’s model on The Legacy reminded us of several other architectural mock-ups that we’ve seen on film and television. As in the Danish series, the use of models in media often advances a plot line and helps flesh out character—revealing the aesthetic proclivities and philosophies of fictional architects. While some mock-ups are serious and true to life, others are deliberately grandiose and absurd to satirize the industry. From the film adaptation of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainheadto the Simpsons spoof of Frank Gehry, check out our favorite manifestations of fictional architectural designs.

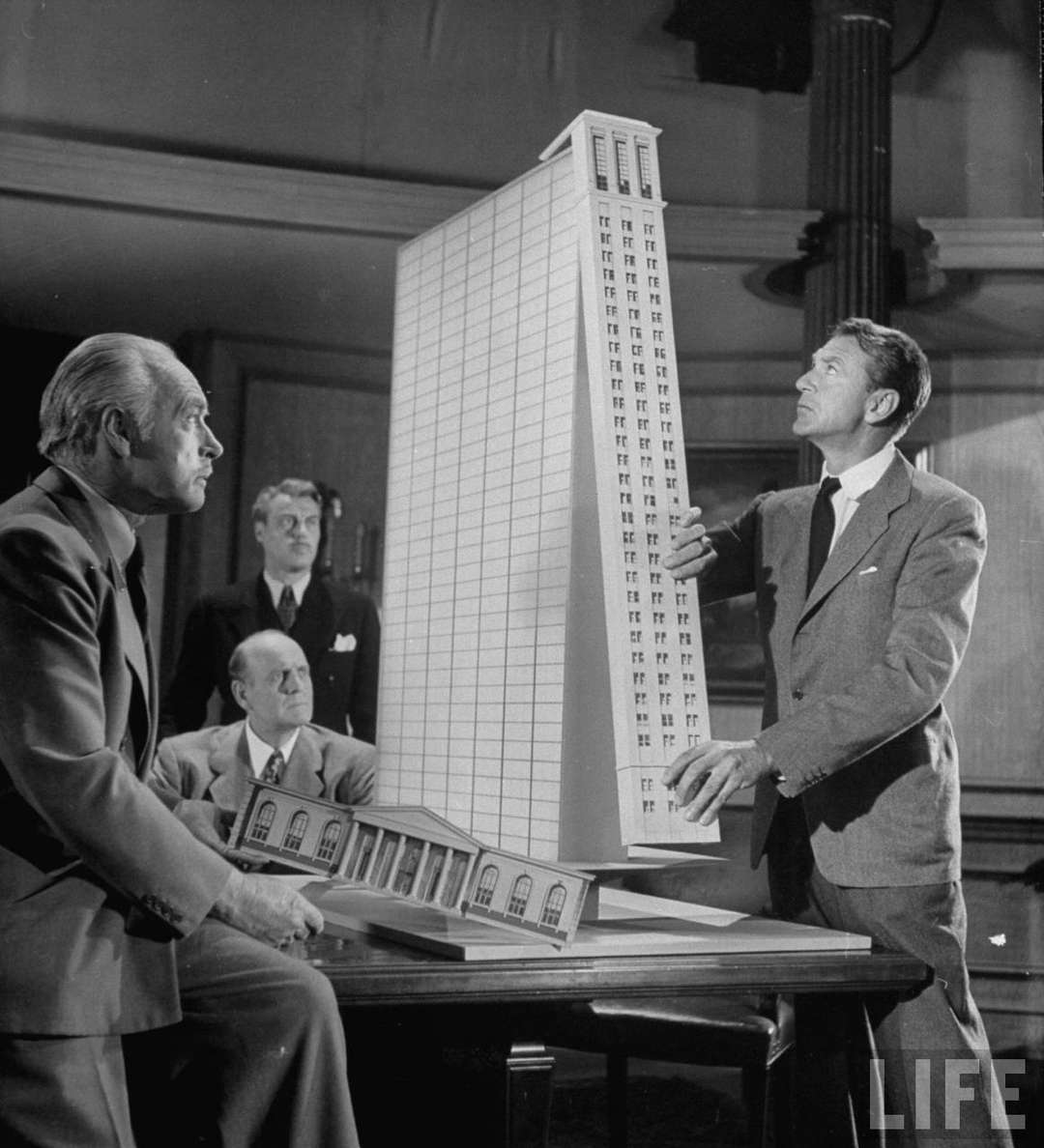

Howard Roark, the egomaniacal architect in Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, is brought to life in the 1948 film adaptation—where you can see a model of his vision Cortlandt Housing Project, a symbol of modernism’s belief in systematic order and functionality. In the film (and book), failing architect Peter Keating begs Roark to help design Cortlandt—to which Roark agrees under the condition that the building be completed exactly as designed and his name kept anonymous. When Roark sees final changes made to his design, he ultimately dynamites the building to prevent the sullying of his vision, which he thought of as a testament to the supremacy of the individual—GAG!

A scene from the 1960s film Beat Girl unintentionally points out how architects can sometimes tread toward delusional visionaries à la Le Corbusier. As an architect points to his model of a forward-thinking complex that he calls “City 2000″—which looks like a hybrid of Corbu’s Plan Voisin and Plan Obus—he claims, “Psychologists have said that man’s neurosis comes from too much contact with other humans. This won’t happen in my city.”

Le mani sulla città – Hands Over the City—Francesco Rosi’s 1960s thriller about property speculation in Naples (really, it’s way more exciting than it sounds)—dozens of planners, politicians, and profiteers gather around a hardcore modernist plan for a new city development. Rossi uses this scene to make a skeptical statement against the patriarchal powers that control the industry.

1972’s Herbie Rides Again brilliantly satirizes the rise of super-tall skyscrapers and apartment blocks when real estate developer Alonzo Hawk unveils the mock-ups for his “Hawk Plaza.” The models are so colossal that the camera must pan up in under to capture the entirety of the complex and a curtain unveils the systematic twin towers.

Steven Martin plays struggling architect Newton Davis in 1992’s romantic comedy The Housesitter. Newton’s reputation for being a straight-laced square matches his architectural designs, as one mock-up looks like a proposal for a new Holiday Inn along a highway.

Richard Gere’s character Vincent, an erudite architect in 1994’s Intersection, finds a particular satisfaction in explaining the “fenestrations” in the model of his Frank Lloyd Wright-like villa to his lover as she lazily lounges in bed, asking, “Is there something that we can drink that will make us two inches tall? Then we can move in.”

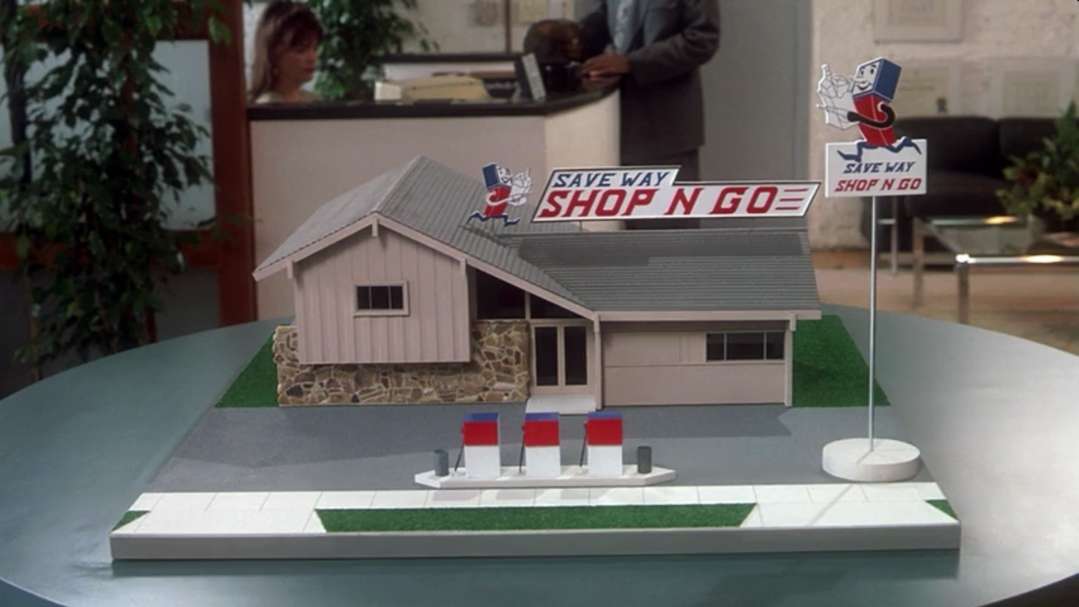

In 1995’s The Brady Bunch Movie, a spoof that places the wholesome 1970s sitcom family in the 1990s, Mike Brady’s boss turns down his request for a salary advance, stating, “Your designs are from another time.” Naively, Mike responds, “That’s kind of you to say, Mr. Phillips. I’ve always thought of my designs as classic as well.” Cut to Mike’s model for a rest station, which features the same design as the classic 1950s California ranch that the Bradys call home.

In 1996’s One Fine Day, Michelle Pfeiffer plays an architect and single mother struggling to succeed in a corporate architecture firm. Although her character’s Cesar Pelli-like model of a development complex seems sure to win over potential clients as she carefully carries it to a presentation, you don’t want to know what happens next.

Simpleminded male model Derek Zoolander (in, of course, Zoolander) has difficulty comprehending how children will be able to fit into the mock-up of “The Derek Zoolander Center For Kids Who Can’t Read Good, And Who Wanna Learn To Do Other Stuff Good Too.” Absurd, kitschy, and crowned by a gigantic, shimmering book, the mock-up is a perfect post-modern trifecta.

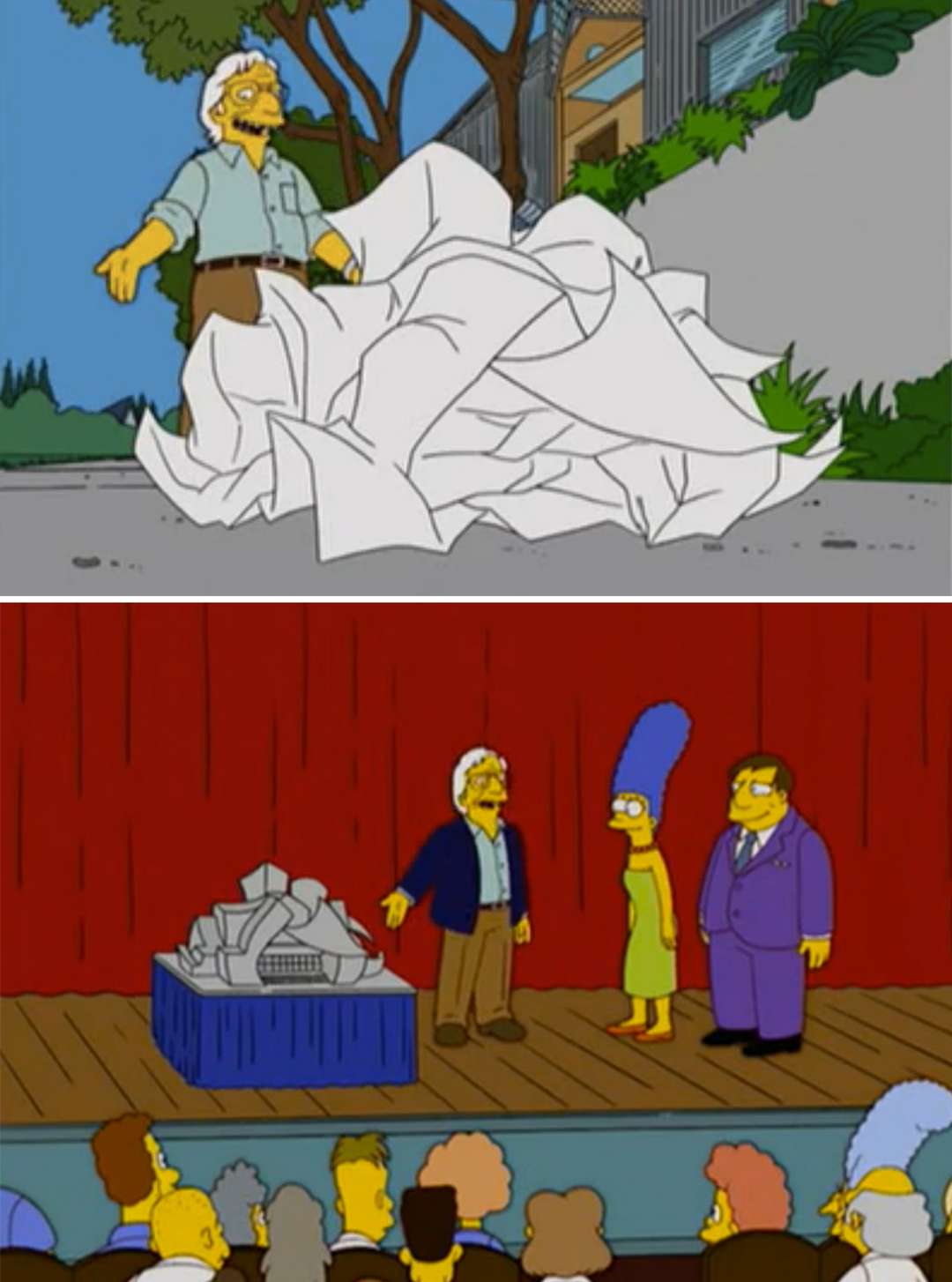

Always at the forefront of satire, The Simpsons manages to humorously lampoon the concept of the “starchitect.” When Marge Simpson writes a letter to Frank Gehry asking him to build a concert hall in Springfield, the famed architect initially discards the piece of paper—then is almost immediately struck with a fit of inspiration, as he stares at the folded sheet and exclaims, “Gehry, you’re a genius!” In the next scene, the model for the Springfield concert hall looks almost exactly like the crumpled piece of paper—and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles.