Of all superheroes, Batman is the one that’s most synonymous with the city he serves. Unlike Superman or Spider-Man, who had their powers thrust upon them, Batman took up the cape totally of his own volition, after deciding that Gotham City’s crime epidemic could only be solved through extralegal means. In this sense, Batman represents the failure of civic institutions: A functional city just wouldn’t need a guy like him. As Commissioner Gordon explains at the end of the 2008 film “The Dark Knight,”“He’s not our hero. He’s a silent guardian.”

But what is this city that is so fundamentally corrupt it requires a “silent guardian?” What does it look like? What architectural style predominates here? Different directors have provided different answers to these questions, each reflecting their own feelings about modern urban life and, perhaps more pertinently, urban decay. With “Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice” bringing Gotham City to theaters once again, the time seems right to revisit the different ways it has been represented in the past.

“Batman” (1989)

Directed by Tim Burton

Via SkyscraperCity

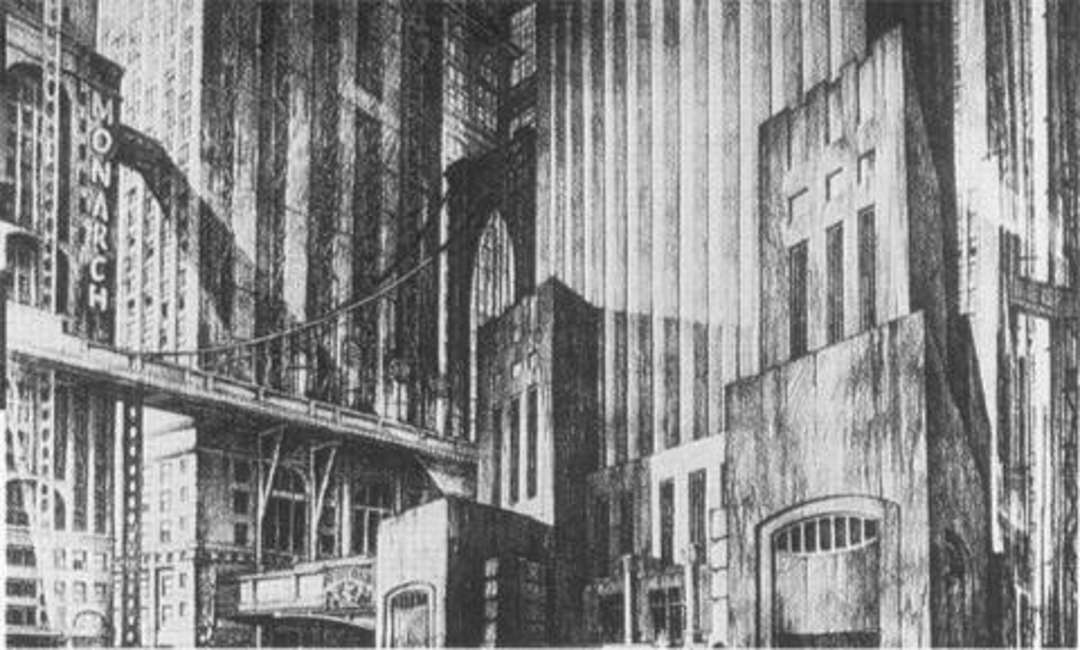

Tim Burton is known as one of the most visually distinctive directors in Hollywood. His films tend to be set in fantastical, gothic locales, and “Batman” is no exception. In this film, Gotham City is depicted as a magnificent art-deco metropolis in decline. The city’s former grandeur can still be glimpsed through the layers of filth and decay, but only dimly. Years of unbridled development and a lack of upkeep have transformed the city into a dingy, smog-ridden dystopia, barely fit for human occupation.

In an interview with Time magazine around the time of the film’s release, production designer Anton Furst described the team’s desire to “make Gotham City the ugliest and bleakest metropolis imaginable. We imagined what New York City might have become without a planning commission. A city run by crime, with a riot of architectural styles. An essay in ugliness. As if hell erupted through the pavement and kept on going.”

Via SkyscraperCity

To achieve this dystopian vision, the filmmakers decided to construct a film set wholly from scratch at Pinewood Studios in England for the scenes set in Gotham. The exterior shots of Wayne Manor were filmed on location at Knebworth House, a massive Tudor Gothic residence in Hertfordshire, England, built in stages between 1813 and 1845.

Like the cacophonous Gotham set, Burton’s Wayne Manor is not intended as a realistic representation of an American millionaire’s residence, but rather as a caricature of extreme opulence. In Burton’s view, Gotham is a city of extremes. “The whole film and mythology of the character is a complete duel of the freaks,” explained Burton. “It’s a fight between two disturbed people.”

Via Internet Movie Cars Database

The director’s mixed feelings toward Batman’s extremism might have influenced his decision to stage the Caped Crusader’s first appearance at Axis Chemicals, a fictional chemical plant filmed at Acton Lane Power Station in London. In a harrowing shot, the word AXIS appears in red neon letters right behind Batman, perhaps implying a relationship between his methods and those of totalitarian regimes.

Film critic Richard Corliss, writing for Time, took this reading even further, noting that numerous visual elements in the film suggest that Burton intends to paint Batman as a fascist figure. “Gotham City, despite being shot on a studio backlot, is literally another character in the script,” he explained. “It has the demeaning presence of German expressionism and fascist architecture, staring down at the citizens.”

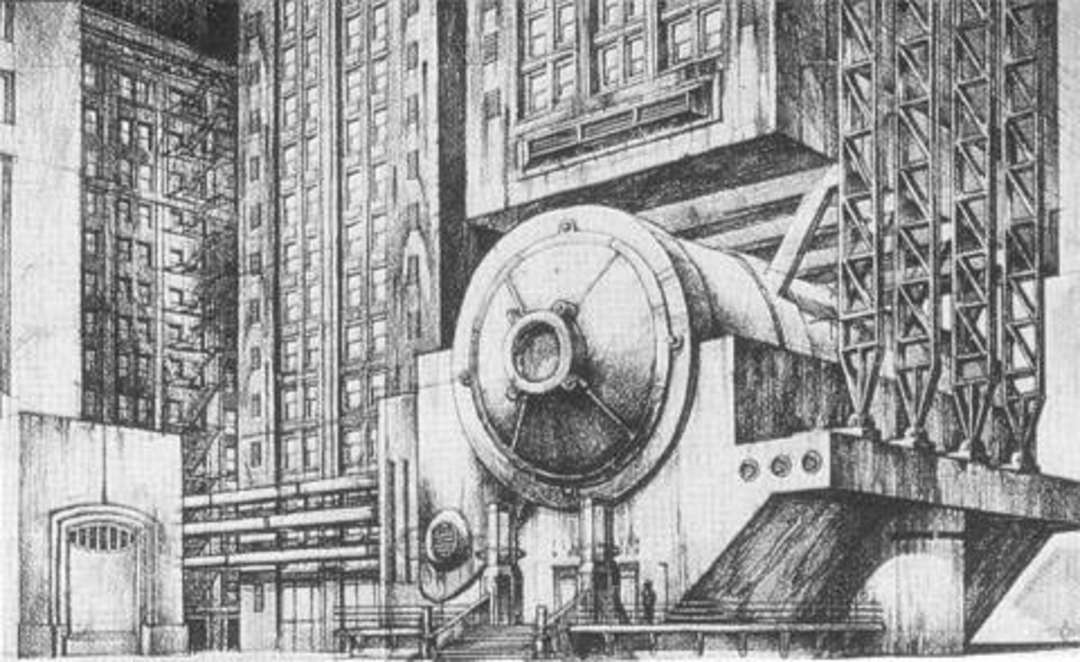

Corliss points to Fritz Lang’s 1927 dystopian film “Metropolis” as an obvious reference point for Burton’s Gotham. This German-expressionist classic features massive, looming art-deco structures that suggest a society controlled by forces totally indifferent to lives of ordinary people. Batman, an eccentric millionaire who works outside the law to impose his own vision of justice on the people of Gotham, could certainly be viewed as the sort of grandiose, undemocratic figure Lang’s film warns against. Then again, with villains like the Joker on the loose, where would Gotham be without its favorite vigilante?

Still from Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” (1927) via 3:AM Magazine

Production designer Anton Furst’s early sketches for the set of “Batman” show the influence of Fritz Lang’s vision of urban impenetrability; via DesignCommunity

“The Dark Knight” (2008)

Directed by Christopher Nolan

A gentrifying Gotham? The Joker stands outside Starbucks on a pristine boulevard; viacamerainthesun.com

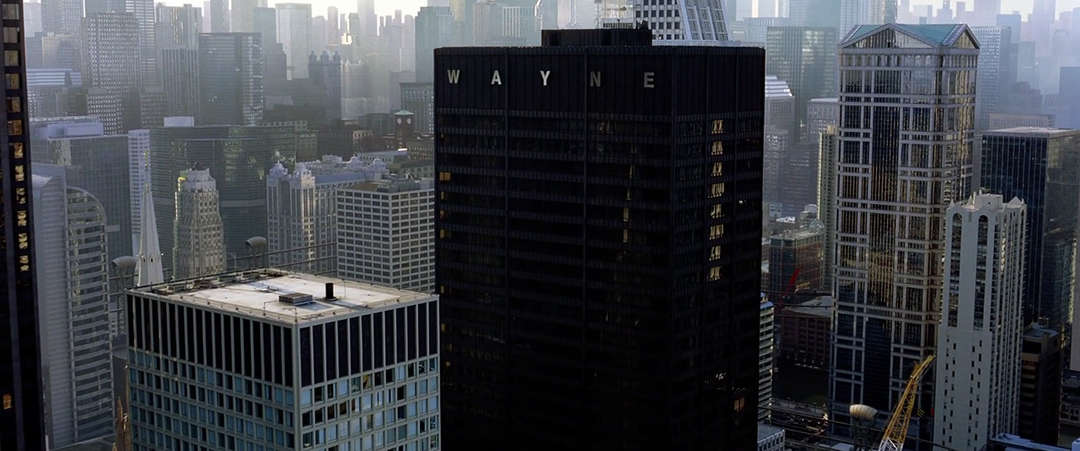

Christopher Nolan’s Gotham City in “The Dark Knight” (2008) is almost the polar opposite of Burton’s. Where Burton’s city was crowded, dingy and chaotic, Nolan’s does not seem especially dysfunctional — at least from the outside. Filmed mostly in Chicago, this Gotham is dominated by wide boulevards and the clean lines of international-style skyscrapers. It does, in fact, look like a realistic American city, and an idealized one at that. The labyrinthine back alleys where Gotham’s criminals usually fester don’t seem to exist here. But, as Batman learns, not even a gleaming metropolis is safe from international crime syndicates or domestic terrorism.

Image via Moviepilot

This sculpture is known to Chicagoans simply as The Picasso. A detailed view of the Richard J. Daley Center can be seen in the background; via Dan DeLuca, Flickr

Nothing underscores the buttoned-up respectability of Nolan’s Gotham more than the decision to place the headquarters of Wayne Enterprises in the Richard J. Daley Center, a classic, international-style skyscraper designed by architect Jacques Brownson. Completed in 1965, it serves as Chicago’s premier Civic Center and is known for its innovative use of Corten steel, a material specially designed to age gracefully by strengthening as it rusts. Corten steel is responsible for the structure’s trademark red-brown color. The plaza adjacent to this building is home to an untitled Picasso sculpture — also made of Corten steel — that is one of Chicago’s most recognizable pieces of public art. Very classy, Mr. Wayne.

The Richard J. Daley Center isn’t the only sleek modernist Wayne property in “The Dark Knight.” After the destruction of Wayne Manor in the film’s prequel, “Batman Begins” (2005), Bruce Wayne has moved into a fabulous high-rise penthouse with wraparound views of the city. The room used for filming is actually the ballroom at the Wyndham Grand Chicago Riverfront Hotel.

Image via MovieMaps

As one can surmise from his tastefully decorated penthouse, Nolan’s Batman is not nearly as outré a hero as Burton’s. Wayne’s role as Batman almost seems like a natural extension of his job as the head of a defense technology company whose products include all-terrain tanks and a surveillance system that works by assembling echo-location data from cellphones.

Thematically, the film is less preoccupied with 20th-century totalitarianism than it is with more contemporary questions of how to balance democratic ideals against the pressing threat of terrorism, represented by Heath Ledger’s anarchist-minded Joker. On this topic, the film comes to a mixed conclusion: While Batman destroys the echo-location surveillance machine at the end — citing privacy concerns — he and Gordon agree to cover up a series of murders committed by the District Attorney in order to preserve the people’s faith in government. While Nolan’s sleek Gotham is not the clearly corrupt, dissembling metropolis of Burton’s film, the conclusion of the “The Dark Knight” suggests its apparent stability may just be a façade. The city’s secrets run too deep.

“Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice” (2016)

Directed by Zack Snyder

Lex Luthor contemplates the distant Gotham skyline from a Metropolis rooftop; via Digital Spy

In “Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice” (2016), director Zack Snyder places Gotham and Superman’s home city Metropolis directly across from one another, on opposite sides of a small body of water. “The big rule that we broke is that we put Gotham and Metropolis right next to each other,” Snyder explained. “It made sense to us and worked for our story that they were kind of sister cities across a big bay. It’s like Oakland and San Francisco, kind of.”

Bruce Wayne responds to a crisis at Wayne Enterprises … in Metropolis; via Screen Rant

Few scenes in this film are set in Gotham, but the city still figures heavily as a felt absence in the film, a foil to the more frequently featured Metropolis. When Bruce Wayne needs to attend a gala, it’s Metropolis he travels to. Similarly, in a flashback, we see Wayne rush to Metropolis to help his employees vacate their building as it comes under fire during an alien attack. Even Wayne Enterprises, it seems, is now headquartered in Metropolis. A seat of media and big business, Metropolis feels like the center of the world while Gotham languishes in the shadows.

The gloomy, abandoned warehouse that kicks off the film’s last act may be a perfect metaphor for Gotham City; via Bustle

We do visit Gotham at the very end: When Batman lures Superman into a final confrontation, he chooses to do so on his home turf, in an abandoned warehouse on the Gotham waterfront. And really, this might be the most fitting metaphor of all for Gotham City. Remember, this was the city the world abandoned. In every version of the Batman myth, we learn that corrupt or otherwise ineffective politicians allowed Gotham to fall into the hands of thugs, gangsters and even homicidal maniacs like the Joker.

Batman exists because a failing city — an abandoned city — requires a deus ex machina to pull it back from the brink. The job is dangerous, thankless and, in “Batman v Superman,” even unglamorous, as Batman feels duty-bound to try to kill Superman, America’s golden boy. But it’s necessary, of course … at least according to Batman.