An end of an era came in December 2012 when Oscar Niemeyer passed away. For many, Niemeyer’s name was synonymous with modernism in Brazil, or even in Latin America. In his 104 years he managed to build dozens of projects, gaining a rare global recognition.

However, Niemeyer was not the only modernist architect working in Brazil, which is full of elegant, imaginative buildings from other home-grown masters. Following our recent dig into Mexican modernism, we now take a look at some of Brazil’s lesser-known modernists.

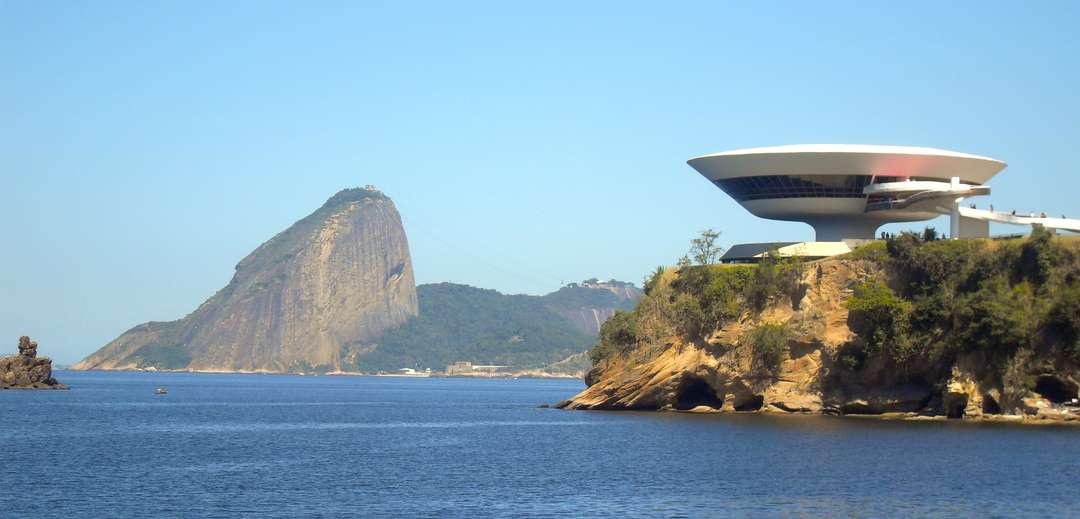

Oscar Niemeyer – a name that is synonymous with Brazilian modernism. Top: Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in Pampulha, Belo Horizonte. Bottom: Mac de Niteroi Museum in Rio de Janeiro. Photos: Via +Wikimedia

OSCAR NIEMEYER

Niemeyer was born and raised in Rio de Janeiro along with his five siblings. His father was a graphic designers who recognized his son’s visual talent early on. The young Oscar was sent to study at the National School of Fine Arts, where he was trained as an architect. Fortunately for him, the school’s dean, architect Lucio Costa, noticed him. Costa “adopted” Niemeyer and included him in a team of designers who worked on the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio (a project for which Le Corbusier was a consultant). Funnily enough, the building today is associated with Niemeyer more than with any other architect.

Though the two collaborated again later, Neimeyer soon outgrew his mentor. Through the 1940s and 50s, he shaped his free-form modernist language, a language so strong and communicative it soon became synonymous with Brazil’s modernity and Latin America’s advancement.

Niemeyer belonged to the far-left parties in Brazil and for most of his adult life was associated with Brazilian communism. His most well-known project is in Brasilia, where in 1956 he designed a series of governmental buildings. Niemeyer was active in other parts of the world, too; he participated in the planning of the UN Headquarters in New York, planned a desert-city and a university tower in Israel, and much more. Like Le Corbusier, he was one of the first “global” architects. In 1988, he was awarded the Pritzker Prize. Later in 2003, he designed the summer pavilion for London’s Serpentine Gallery. His buildings are instantly recognizable: They exhibit an outstanding continuity of design in colors, daring geometry, and extravagant simplicity.

Niemeyer’s designs in Brasilia, 1956: an architectural project of international importance. Lucio Costa was in charge of the project’s master plan, yet his name is hardly as commonly associated with it as is Niemeyer’s. Photo via

Niemeyer’s pavilion for the Serpentine Gallery in London, 2003. Continuity in design. Photo via

A view of the UN Headquarters on the East River bank in Manhattan—a project designed by Niemeyer with Le Corbusier, Harrison and Abramovitz and others in 1952. Photo via

LUCIO COSTA

Architect and urban planner Lucio Costa was director of Niemeyer’s university, the National School of Fine Arts in Rio De Janeiro, from 1930 on. This was the beginning of a complex, lengthy professional relationship between the two. After hiring Niemeyer for the planning of the Ministry of Education and Health, a massive modernist project in the heart of Rio, Costa and Niemeyer collaborated again on the project of Brasilia, for which Costa was the master-planner and Niemeyer a central designer. Another mutual project was their Brazil Pavilion at the New York City World’s Fair, 1939. With his political connections, Costa pushed for the modernization of Brazilian architecture his whole life, and is responsible for the approval and execution of many of the country’s modern assets.

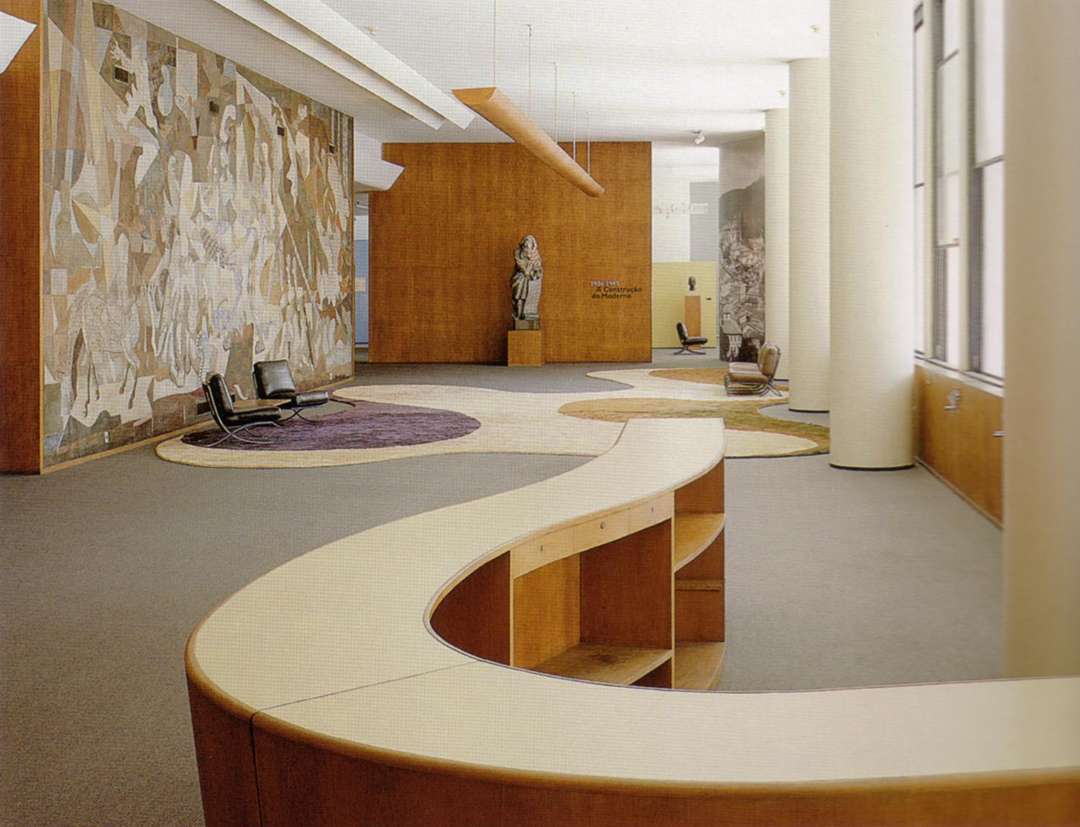

Interior lobby, ground-floor colonnade, and garden-terrace of Rio’s Ministry of Education and Health, designed by Lucio Costa and his (then) ambitious intern Oscar Niemeyer. The garden terrace was designed in collaboration with landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx (see below). Photos via and viaflickr

Brazil’s Pavilion at the World’s Fair in New York City, 1939, by Costa and Niemeyer. Already a distinct modernist language. Photo via

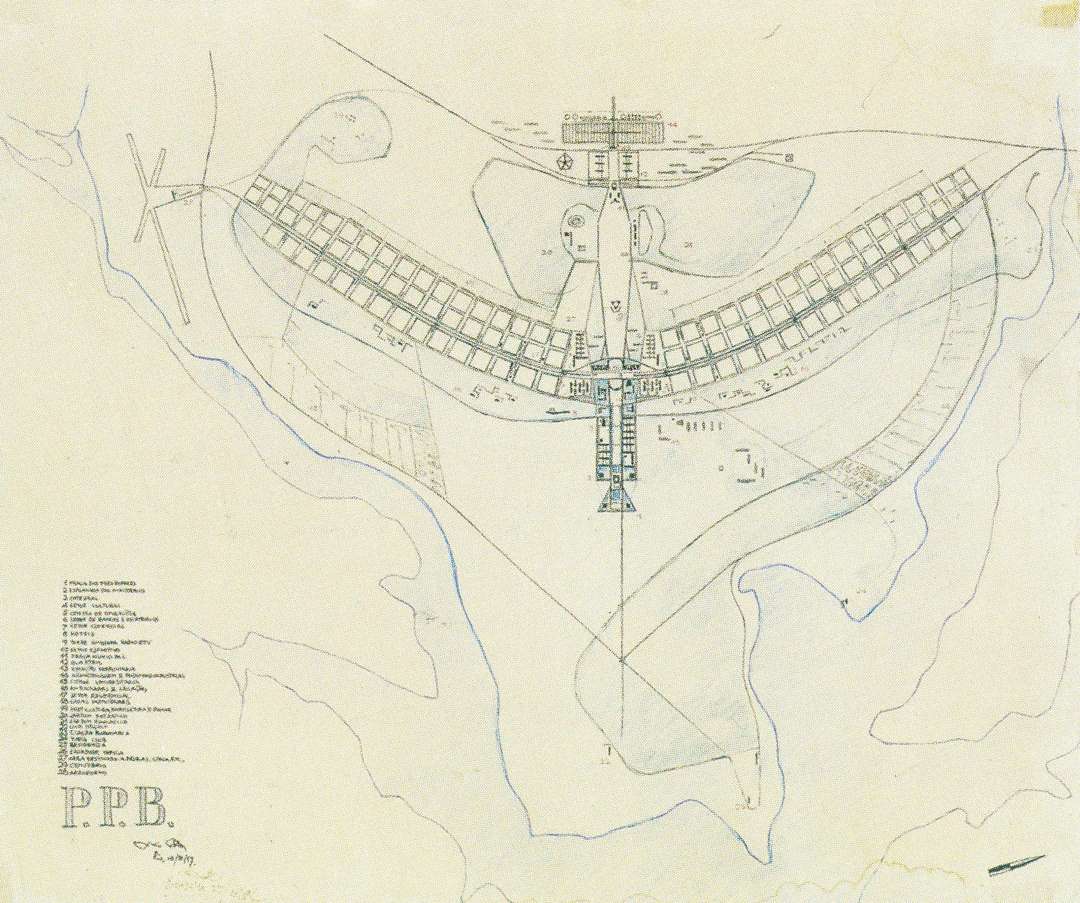

Costa’s plan for Brasilia: A modern utopia. Image via

JOAO BATISTA VILANOVA ARTIGAS

Artigas was a prominent figure as a practicing architect and educator in Brazil. Born in Curitiba, he studied at the Polytechnic School of the Sao Paulo University, where he later taught. In the 1940s, he was among a group of professors that pushed to establish the university’s architecture faculty. The faculty’s building was designed by him with Carlos Cascaldi in 1960. Other notable projects of his include his own home in Sao Paulo, the Itanhaém School, the Guarulhos Building-blocks, and the Santapaula Marina.

Top: Edificio FAU-USP (Architecture Faculty at the University of Sao Paulo) by Artigas and Carlos Cascaldi. Photo via. Bottom: Artigas’s own residence in Sao Paulo. Photo via.

PAULO MENDES DA ROCHA

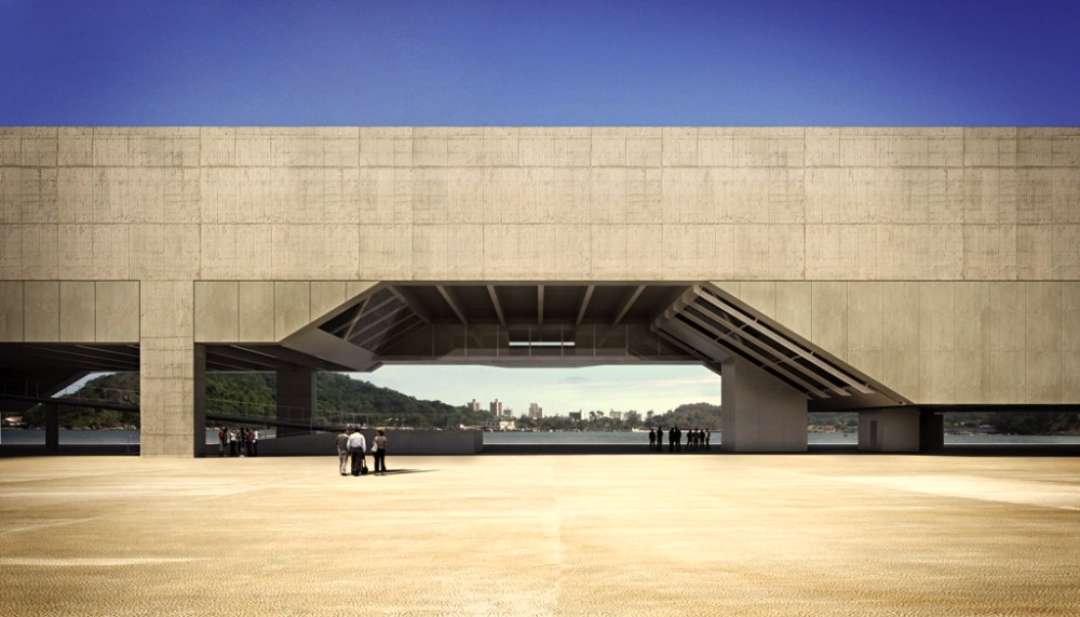

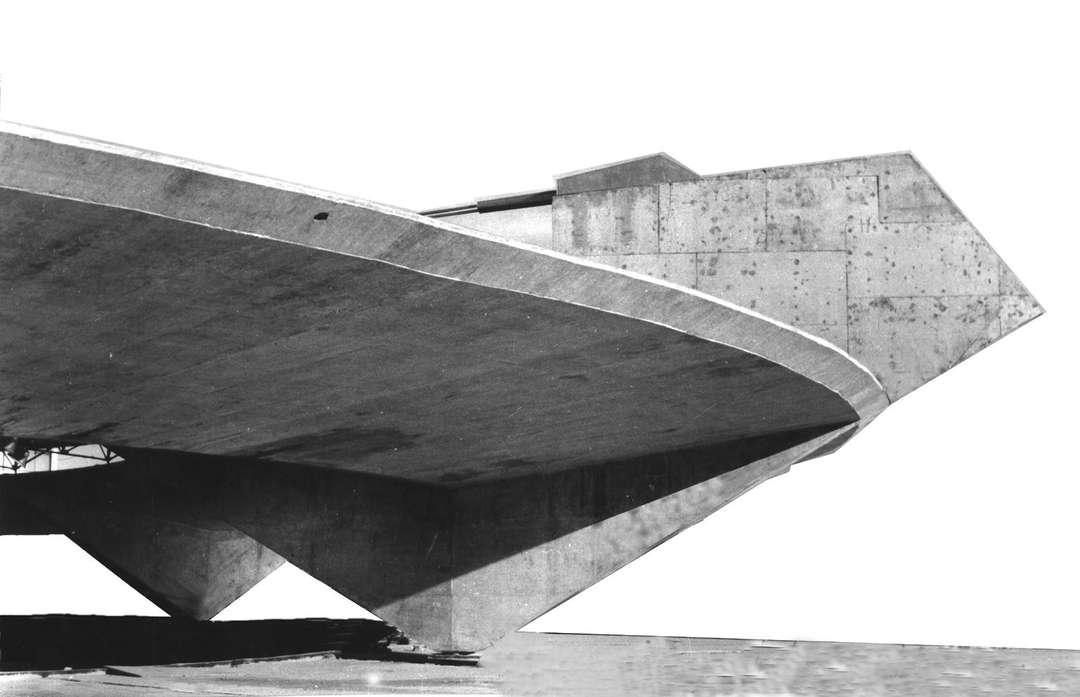

Though not nearly as famous as Niemeyer, Paulo Mendes Da Rocha (born 1928) is one of Brazil’s better-known architects, receiving the Mies Van Der Rohe Prize in 2000 and the Pritzker Prize in 2006. Mendes Da Rocha practiced “Brazilian Brutalism”—a method of concrete usage to produce casts inexpensively and quickly. His most striking projects include Cais das Artes in Vitoria and the Gerassi House, the Saint Peter Chapel, and the Pinacotheca, all in Sao Paulo.

The “Cais Des Artes” by Mendes Da Rocha and architecture office METRO. Photo via

A brutalist detail of one of Mendes Da Rocha’s early works, the Gymnasium in the Paulistano Athletics Club of Sao Paulo. Photo via

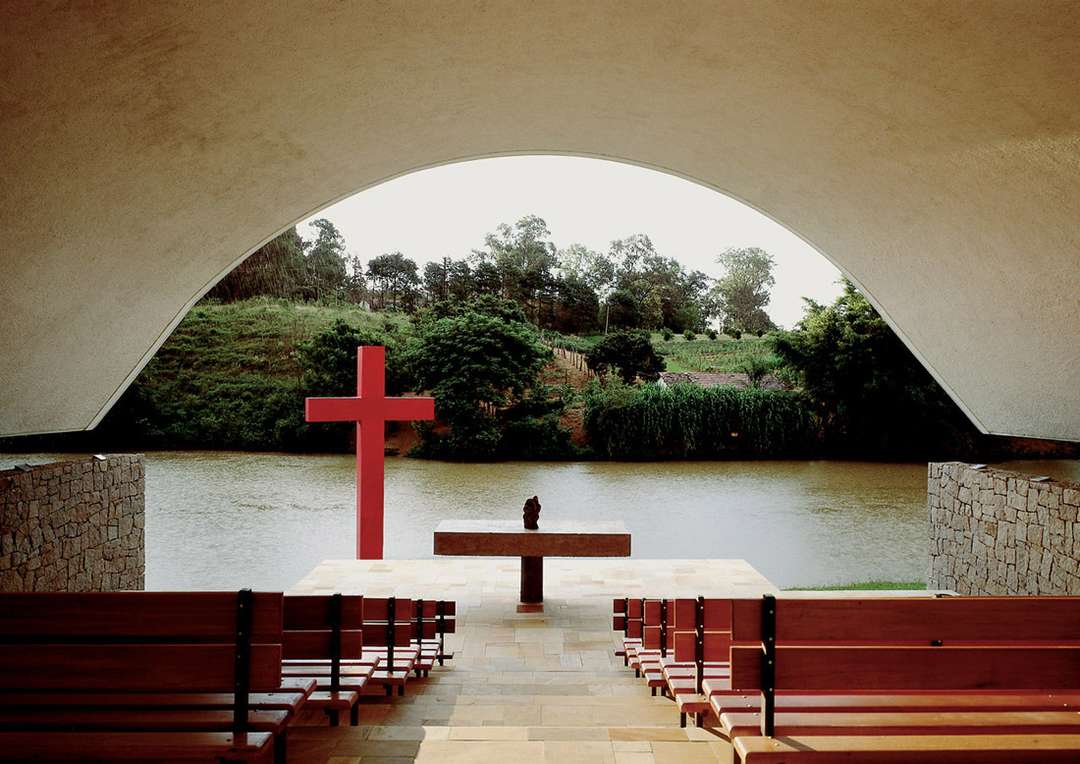

Chapel of Saint Peter, Campos de Jordão, São Paulo, Brazil, 1987 by Mendes Da Rocha. Photo via

The Brazilian Museum of Sculpture, São Paulo, Brazil, 1988. Photo via

JOSE AUGUSTO BELLUCI

A distant relative of Felix Candela in style, Jose Augusto Belluci is a Brazilian modernist with few still-existing works. His cathedral of Maringa, however, is one of the country’s mid-century icons.

The Cathedral of Maringa by Belluci (1959-1972). A strange, but loved, piece of mid-century modernism. Photo via

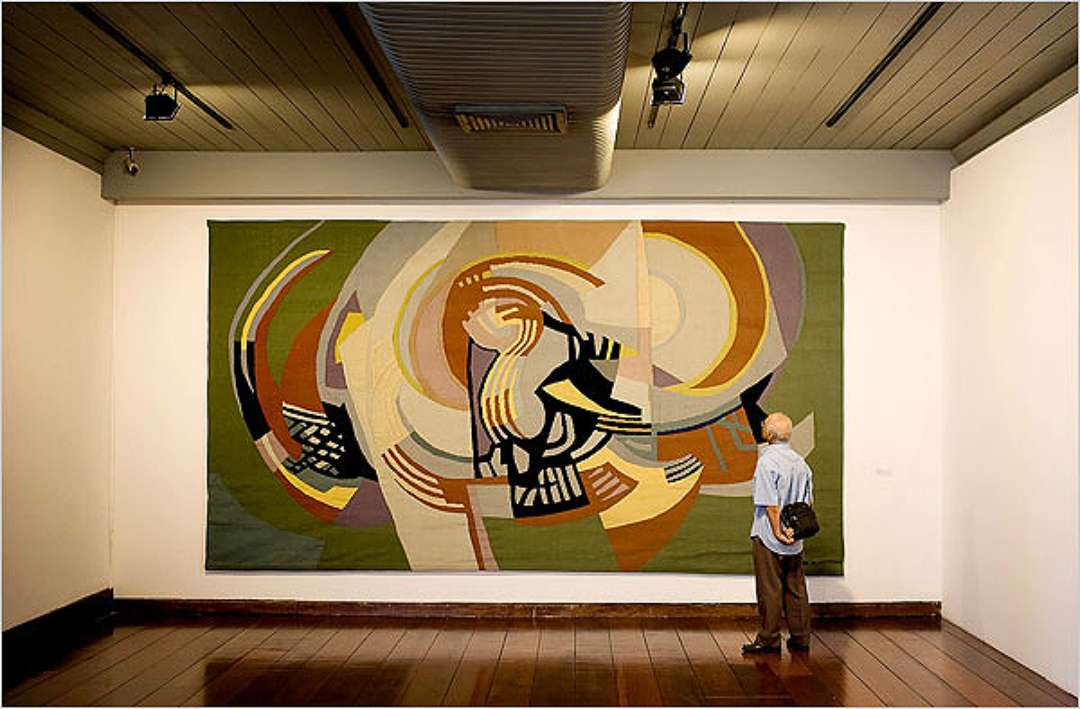

ROBERTO BURLE MARX

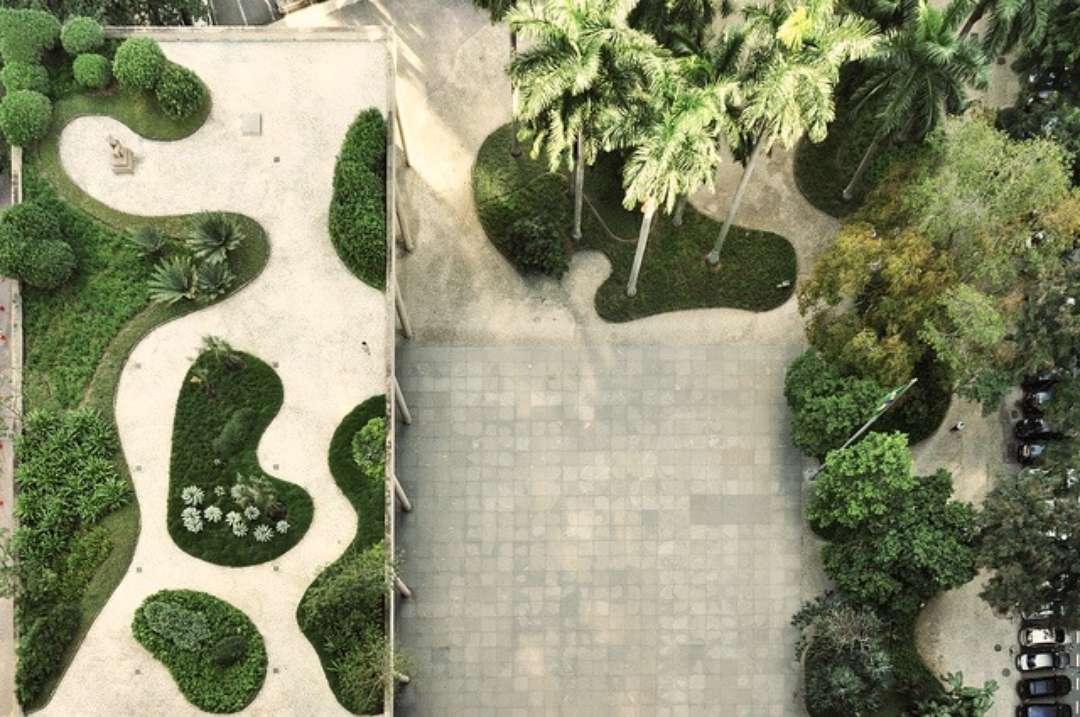

Burle Marx, born 1909, was perhaps Brazil’s most notable landscape architect and artist in the 20th century. His vision was clear: He took Brazil’s tropical fauna and gave it grammar and discipline. Burle Marx collaborated with Niemeyer and Costa on Rio’s Ministry of Education and Health, designing the building’s gardens. His additions to the project were so noticeable, so modern and striking, that his name became as known as those of the architects. Burle Marx was also a painting and a jewelry designer. An exhibition marking his 100th birthday was exhibited in Rio De Janeiro and Sao Paulo in 2009.

House: Niemeyer. Landscape: Burle Marx. A private residence in Petropolis, Brazil.

Another collaboration with Niemeyer, this time in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brasilia.

The Copacabana boardwalk by Burle Marx, later copied in different places around the world. All photosvia

Museum visitors viewing paintings by the multitalented Burle Marx. Photos via

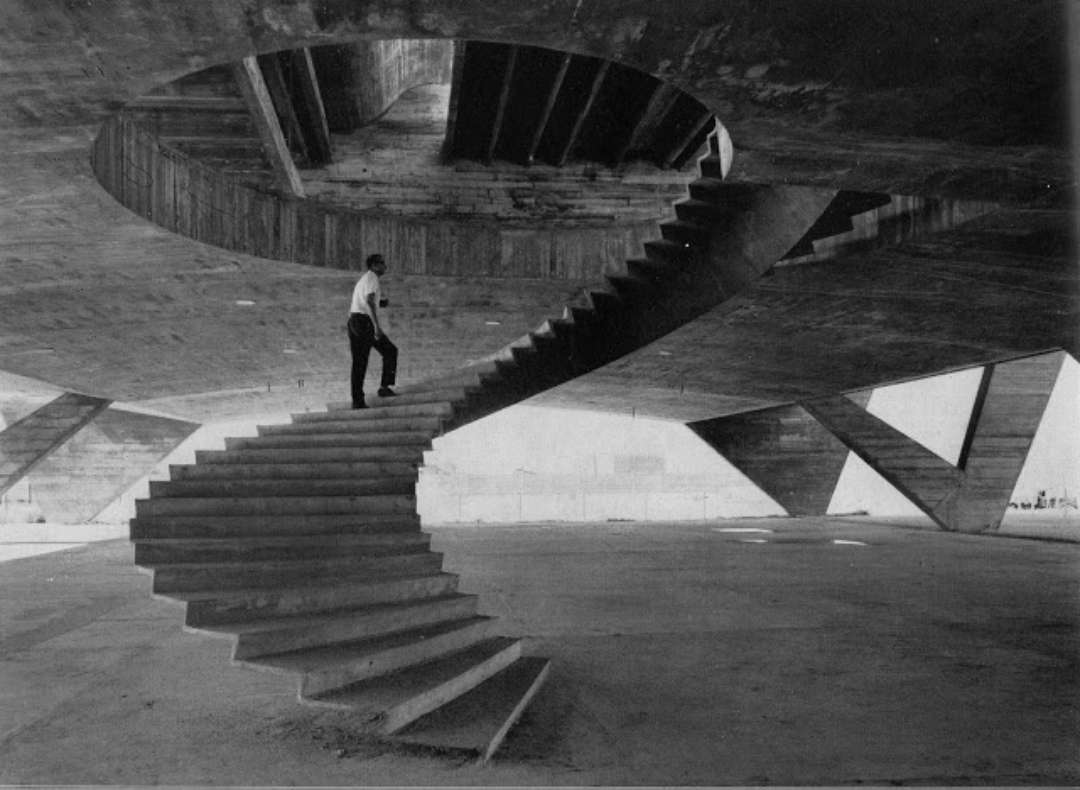

AFFONSO EDUARDO REIDY

Though his career was brief, Affonso Eduardo Reidy was a strong force within Brazil’s push for modernism. As a teacher in the National School of Fine Arts, he worked alongside Lucio Costa to develop a distinct architectural school of Rio De Janeiro. His boldest project was the Museum of Modern Art of Rio, a rib-shape building made of exposed concrete.

A sensual housing block (“Conjunto Residencial Prefeito Mendes de Moraes”) in Rio, designed by Reidy in 1947. Photo via

The Museum of Modern Art in Rio (facade and staircase detail). Photos via flickr and via

RINO LEVI

Born in Sao Paulo, Rino Levi was a Brazilian of Italian descent. In 1926, he graduated from the Superior School of Architecture in Rome, where he studied after a brief period in the architecture department of the Brera Academy in Milan. Once returning to Brazil, Levi started working in different firms and later established his own practice. Influenced by Italian modernism, Levi’s designs are colorful and simple, less extravagant than his contemporaries.

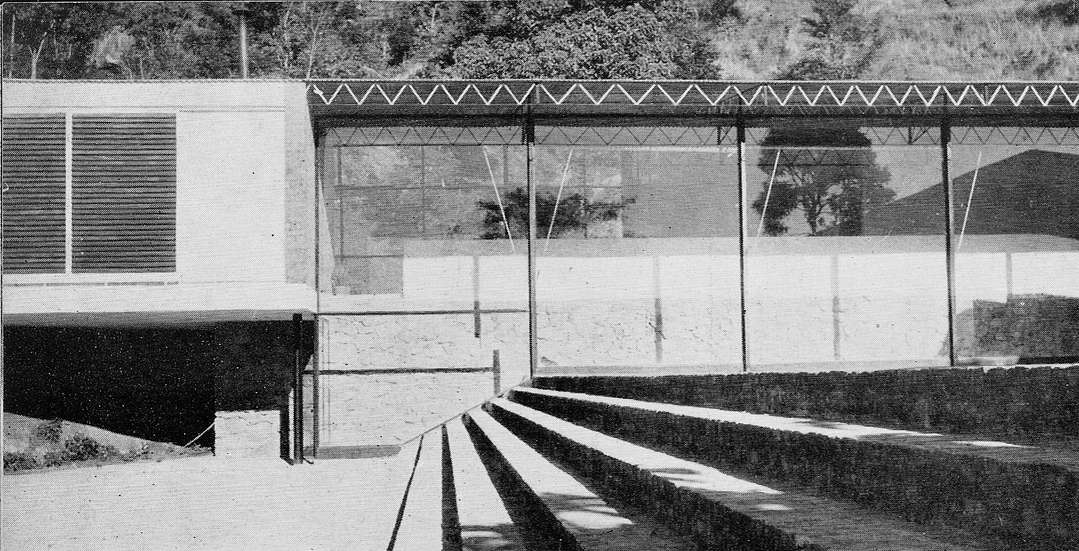

One of Levi’s iconic designs is this residence, designed for Olivo Gomes. Photos via

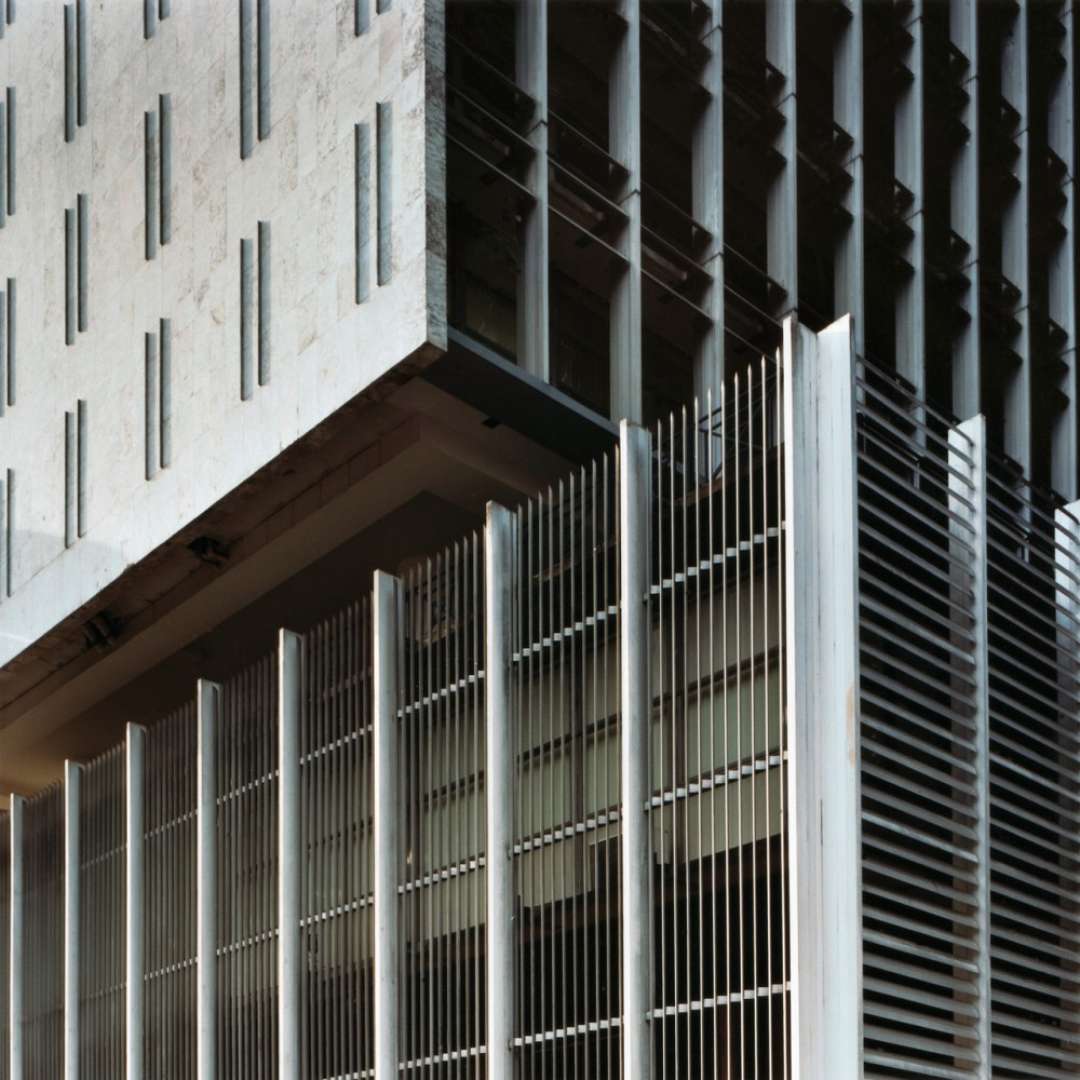

Intricate facade compositions in Rino Levi’s skyscraper – Banco Sudamericano de Brasil – in Sao Paulo. Photo via

LINA BO BARDI

Lina Bo Bardi, born in Italy, was one of Brazil’s most prolific modernist architects. Before moving to Brazil, she was active as an architect, writer, and illustrator, and even ran Domus magazine in Milan for a few years. After her arrival in Rio De Janeiro, 1946, Bo Bardi established her own practice. She developed a large body of work and a distinct language, using exposed concrete in sculptural ways and contrasting it with bright, warm colors. Bo Bardi’s work was shown at the Venice Architecture Biennale and the British Council in London; she was also was the focus of an exhibition curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist (in two buildings she herself designed).

Lina Bo Bardi’s masterpiece, the SESC Pompéia Building, photographed by Pedro Kok. Photo via

The Museum of Art of Sao Paulo, designed as a lifted rectangular mass with a red constructive frame. Photo via

Bo Bardi’s Glass House (her own residence) in Mata Atlantica (near Sao Paulo). Photo via

SERGIO BERNARDES

Originally a pilot, Sergio Wladimir Bernardes graduated from the faculty of architecture at the National University of Brazil in 1948. Already as a student, Bernardes caught the attention of the public when a theoretical project of his was published in the French magazine L’Architecture D’Ajourdhui. Later, as a young architect in Rio, he worked with Niemeyer and Costa and by 1951 had already built his first commission, a private home. Of his most eccentric designs are the utopian Hotel Tropical Tambau, as well as a stadium, an airport and some case-study-style houses.

Hotel Tropical Tambau by Sergio Bernardes. A utopian design of socialism and leisure. Photo via

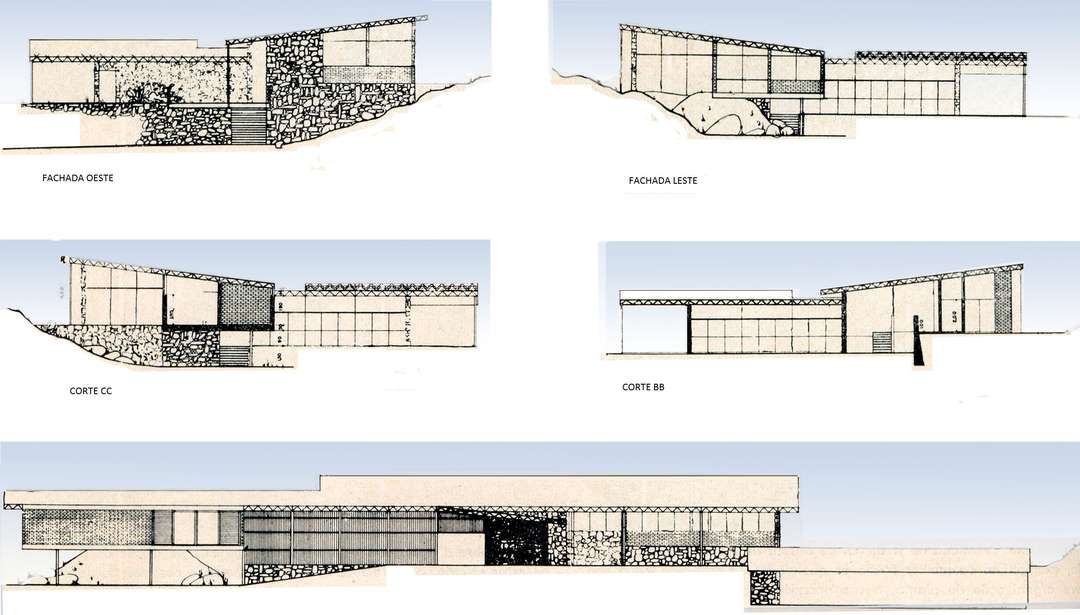

Drawings and a facade of the Lota de Macedo Soares house, designed by Bernardes in Petropolis, Brazil. Drawing via, photo via

ICARO DE CASTRO MELLO

Icaro de Castro Mello was not only an architect; he was also an award-winning athlete. After studying architecture, he founded the Castro Mello firm (still practicing), devoted to the design of sports facilities. Specializing in this area, Castro Mello was able to execute numerous stadiums and other arenas in Brazil, including the national stadium in Brasilia.

Top: The Stadium of the University of Sao Paulo. Bottom: The National Stadium in Brasilia. Photo via andvia

OSVALDO BRATKE

Mainly active in the residential-project sphere, Bratke was in charge of building a viaduct in Sao Paulo followed by private residences around the city. His most central project was the house of Oscar Americano, completed in 1953.

Inside and out at the residence of Oscar Americano. Photos via

DECCIO TOZZI

Though much younger than most of the honorary members above, Deccio Tozzi (born 1936) was already active in the 1960s and continued the modern movement into the 21st century. His 2002 project, the Veneza Farm Chapel, could have easily been built 50 years before.

Deccio Tozzi’s school “Jardim Ipê”, 1965. Photo via

The Veneza Farm Chapel by Tozzi. Photo via

Recommended books: Brazil’s Modern Architecture by Phaidon Press, When Brazil Was Modern by Princeton Architectural Press, and Oscar Niemeyer and Brazilian Free-Form Modernism by David Underwood.