The debate over whether architectural competitions are a worthwhile endeavor for young practices has been raging for a number of years: Modative blogger Derek Leavitt wrote a provocative piece in 2010 lamenting the folly of open ideas competitions, which spurred Archdaily’s Karen Cliento to compose a spirited counter-argument. Despite the debate, one thing is for sure — if your practice is participating in a design competition, you want to give yourself the best possible chance of coming out on top. Here are a few ways to maximize the effectiveness of your entry.

1. Choose The Right Competition

There exist a plethora of what Leavitt scathingly referred to as “fake” competitions, otherwise known as “ideas” competitions. These can be tempting by virtue of their imaginatively framed, ambitious briefs that encourage designers to dream up a utopian vision that solves the world’s greatest socioeconomic problems. The eVolo skyscraper competition is a personal favorite of mine.

However, if you are serious about including competition participation in your firm’s business plan, you have to look at competitions that have a legitimate end product. Is the contest to win a real commission? What is the likelihood that the winning entry will get built? For competitions grounded in reality, check out government websites—there is a least some hope that the commissions there have funding in place and that your winning idea will be transformed from render to reality.

2. Do Your Homework

Once you’ve worked out which competition is right for you, begin with a forensic analysis of the brief: if the project’s location and program are specified, investigate them with the same rigor as your best “real-world” commissions. Daniel Libeskind beat out 164 other entries to win the commission for the Jewish Museum in Berlin, largely due to his intimate knowledge of the history and profound connotations of the site.

Some research into the organizers of the competition can also prove fruitful; you can often find out what they have previously commissioned and begin to understand their priorities in terms of design approach and programmatic needs. This results in an entry that’s less like a shot in the dark and more like an informed proposal for a familiar client.

3. The 30-Second Rule

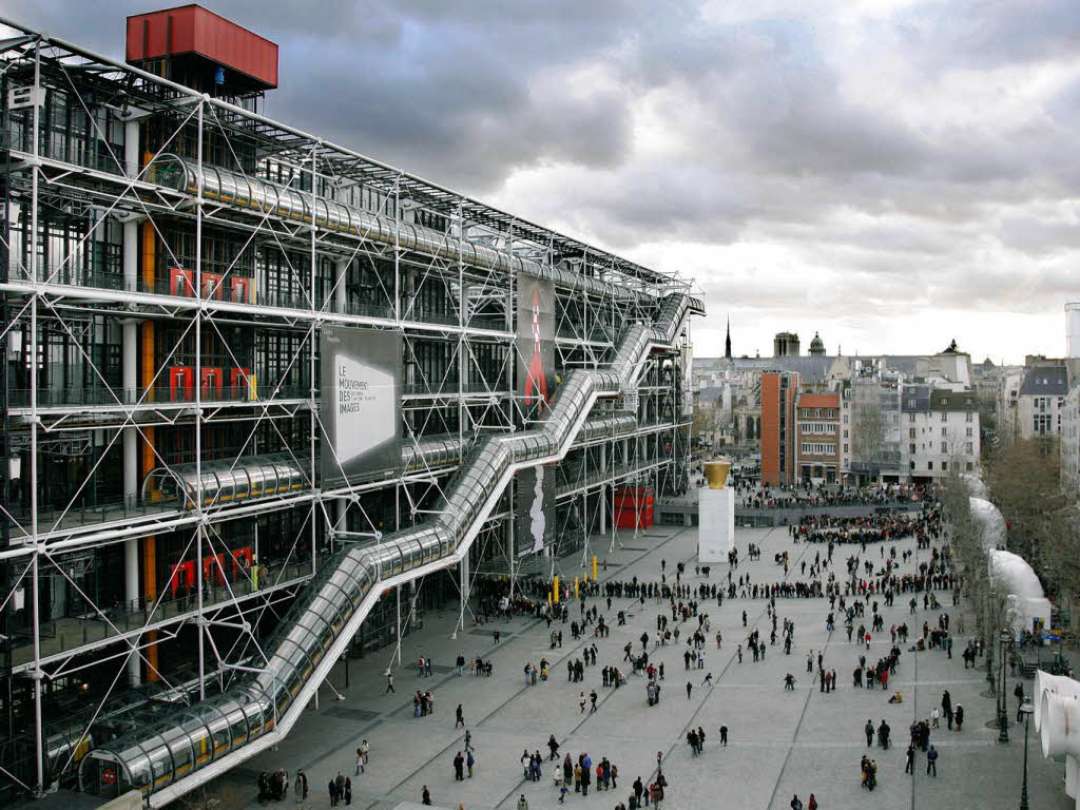

The competition to design the Pompidou Centre, won by the dynamic duo Piano and Rogers, attracted a massive 681 entries, and many contests have submissions numbering in the four figures. This means the jury will have limited time to cast their critical eye over each presentation board, so instant impact is crucial.

A great way to accomplish this is with a central “killer” image that will ensure your entry jumps out from the others; my personal preference is for either a) a dramatic, wide-angle CGI perspective, or b) a beautifully detailed section drawing. If this image can communicate the overriding principles of your concept in a powerful manner, the jury will be placing it on their shortlist in no time.

Image via Plus Mood.

4. Mix Up Your Medium

In addition to the sections and CGIs described above, plans and elevations can be wonderfully effective tools to communicate your designs to clients. However, when displaying your wares for a discerning jury, consider mixing it up to capture their attention. Make a model, take some well-lit photographs, and then add further details using your software of choice; this results in images with an added element of texture and materiality that will give your presentation an unusual edge.

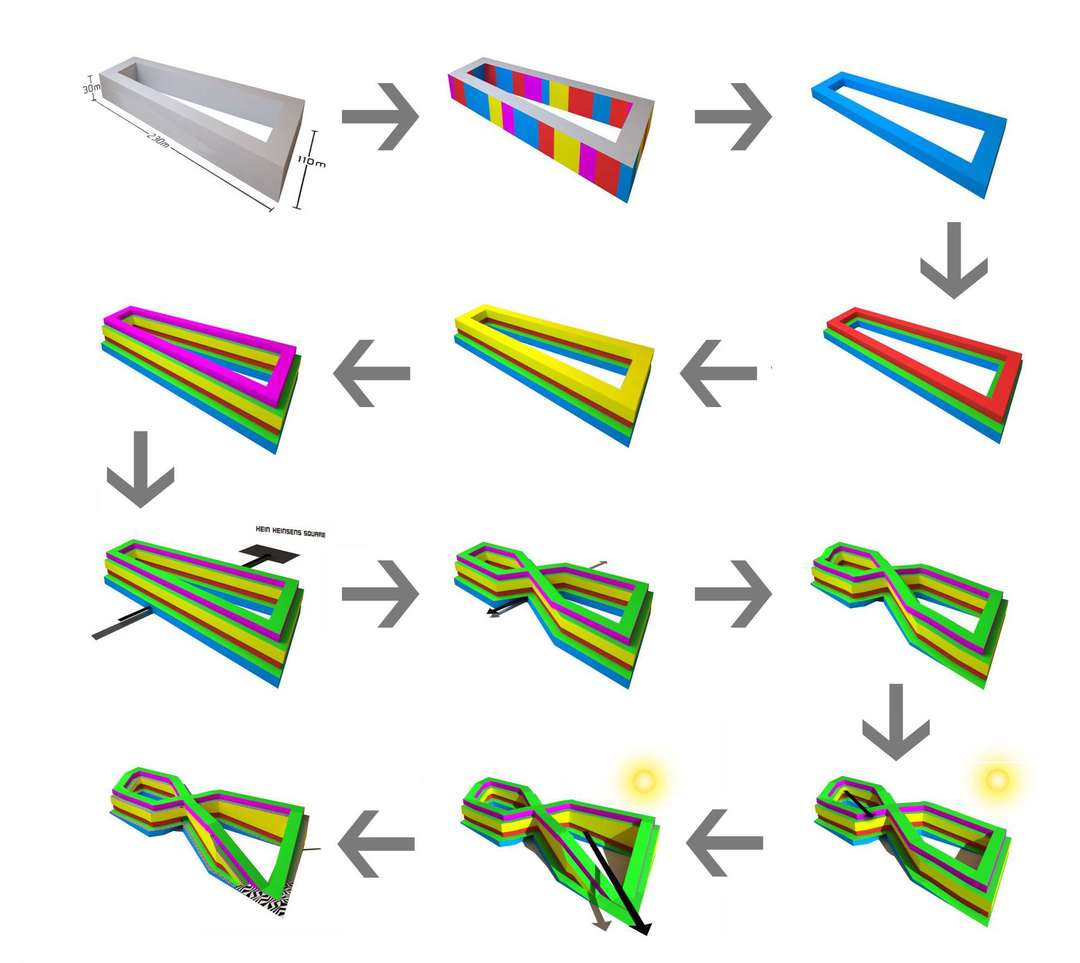

Another method is to use the favorite graphic medium of a certain Mr. Bjarke Ingels: sequential diagrams. As a visual story teller, these can help reduce the necessary explanatory text, distilling the presentation to just one or two boards.

5. Invite Guest Critics

Competition deadlines tend to be tight, and participants spend an intensive period getting to grips with their concept and wrestling with how to best present the final product. It is easy to get so close to a project that the concept is much clearer to you than it may be to the jurors, who only get one shot at deciphering it. Therefore, it can be hugely beneficial to invite a guest critic with “fresh eyes” to give their thoughts on your proposal before submission.

Take a close look at the list of jurors—if it includes people outside the field of architecture, find someone similar to cast their eye over your designs. They will have a perspective entirely different from those within the industry, and might just give you an insight you’ve never previously considered.

6. Think Big

Competitions are an opportunity to let loose, and jurors are frequently drawn to proposals that may appear, on first viewing, somewhat outrageous. Large public commissions often seek daring conceptual gestures, with the knowledge that later refinements will ensure the project can be grounded in reality.

Jørn Utzon’s proposal for the Sydney Opera House is a classic example: his practice beat 232 other entrants for the job, as the jury’s imagination was captured by the joyous display of expressionism. Of course, the practicalities of the building’s construction became an infamous struggle, but Utzon’s legacy prevails. So, don’t be afraid—this is your chance to stick your neck out and go big.

7. Make It A Win-Win Situation

The harsh truth is that 99% of competition entries won’t make the grade—in the eyes of the jury, at least. However, even if a proposal doesn’t make the competition shortlist, its life does not have to end there! If you have followed all the steps listed above, you should now have a splendid piece of portfolio material.

It is not uncommon for a competition concept, beautifully presented on a firm’s website, to attract interest from prospective clients. Make sure to market your “defeated” entries with as much zeal as your built projects—even though they remain on the drawing board, they act as fantastic examples of your creative ambition. It can’t hurt to put a few new ideas into your client’s heads!